And one day the king said,

“I dreamt of seven fat cows eaten up by seven skinny ones; and seven green ears of grain and seven others dry.

O chiefs! Tell me the meaning of my dream if you can interpret dreams.”

The Qur’an, 12:43

The king’s troubling dream foretold years of famine ahead. Today, Pakistan’s Seventh Agricultural Census, released in 2025, delivers a warning of its own. The data emerging from this comprehensive survey reveals structural fractures so deep they threaten the foundation of the country’s agricultural economy.

The census statistics are an early warning for the future of Pakistan’s food security and the livelihoods of nearly 40 per cent of its workforce. Analysis of the census data points to seven interconnected crises that could mark the beginning of Pakistan’s own “seven lean years”, threatening the foundation of the country’s rural economy.

Unlike the biblical king who had a Joseph to interpret his dream, Pakistan must decipher these agricultural omens for itself. And the message in the numbers is unmistakable: the coming years will test the resilience of a farming sector already stretched to its breaking point.

The shrinking farm: A crisis of fragmentation

The most alarming trend is that Pakistan’s farms are steadily shrinking. In Punjab’s most fertile districts, a farmer today might inherit three acres. His grandfather, two generations ago, may have worked the same land as a 12-acre plot. The subdivision among heirs with each generation has carved the family holding into pieces that can barely sustain them, let alone generate profit.

The census shows an overwhelming share of farms are now under five acres. This five-acre threshold is critical because it is roughly the minimum size needed for a farmer to afford or efficiently utilise a tractor and other modern machinery. This leaves a majority of farmers trapped, dependent on costly rentals or inefficient manual labour.

Gendered exclusion from agriculture

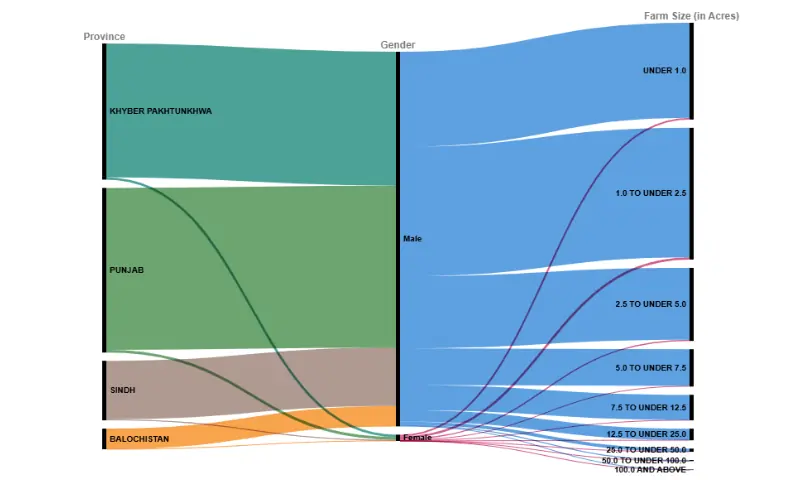

Perhaps the most significant finding is the near-total invisibility of women in formal agricultural ownership. The census examines “female-headed agricultural households” — farms where a woman is the primary owner and decision-maker. These account for less than 1pc of all farms nationwide. The disparity is alarming given that women contribute nearly 68pc of all agricultural labour in Pakistan.

It also reveals a profound gap between law and reality. Both Islamic inheritance law and Pakistan’s legal framework formally entitle women to significant shares of land. However, a 2017-18 Demographic & Health Survey found that 9pc of Pakistani women did not inherit land or a house; only about 1pc inherited agricultural land.

The gap is not rooted in law but in culture. Survey data reveals that families resist giving women property primarily due to deep-seated social attitudes rather than legal barriers. A majority, precisely 58pc, believe that granting women property ownership would lead to family disputes, while 30pc argue that women do not need property in their own name.

Another 12pc question women’s mental capacity to manage property responsibly. Consequently, many daughters are coerced into relinquishing their inheritance rights to their brothers, leaving them without economic assets or financial independence.

The economic cost of this exclusion is staggering. If women controlled the land they are legally owed, they would hold roughly a quarter of Pakistan’s farmland. Instead, this massive economic potential remains untapped, perpetuating rural poverty. From a behavioural perspective, it is futile to expect earnest involvement from women in farming if there is no incentive to eventually inherit the land.

The high-risk gamble of crop specialisation

Pakistan’s agricultural geography shows a pattern of heavy concentration rather than true regional diversity. Wheat dominates across most districts, while rice, maize, and other crops appear only in smaller, localised pockets.

This lack of diversification may simplify production systems and reinforce comparative advantage in key areas, but it also magnifies vulnerability. Heavy dependence on a single crop leaves entire districts exposed to market volatility, climate shocks, and pest or disease outbreaks.

The lessons from abroad are stark. In the mid-20th century, Panama disease Race 1 wiped out the Gros Michel banana across the Americas, collapsing national export industries built on a single variety. Pakistan’s reliance on wheat carries a similar danger. A single well-placed shock could unravel both local economies and national food security when entire regions stake everything on one crop.

The seven deadly signs

The census data points to seven interconnected crises. These are not separate problems; they amplify each other.

A farmer on a tiny, fragmented plot (problem 1) cannot afford to dig a deeper well when groundwater vanishes (problem 2). This makes him more vulnerable to climate shocks (problem 3). To survive, he borrows from a middleman at exploitative rates (problem 7), trapping him in permanent debt. Seeing no future on the land, his sons migrate abroad (problem 5).

-

The fragmentation crisis: As noted, the 12-acre farm from 1970 has become a 3-acre plot today. It is too small to be profitable and too small to be mechanised effectively. In Punjab’s most fertile districts, the average farm size has dropped below five acres, barely enough to support a family, let alone invest in modern farming techniques.

-

The water scarcity shadow: Farmers rely on two main sources — ageing canals and tubewells that pump groundwater. But those groundwater tables are dropping. In parts of Punjab, farmers must now dig 90 feet for water that was at 30 feet two decades ago. Others, in rain-fed (or Barani) areas, are at the mercy of increasingly unpredictable monsoons.

-

Climate vulnerability: Wheat, Pakistan’s staple, needs cool nights in March to mature properly. But as spring temperatures get warmer, yields are already falling. Farmers in rice zones face the opposite — floods one year, drought the next. Poorer farmers, particularly in the most overlooked districts of Pakistan, rely on sailaba irrigation (using seasonal flood waters), a practice that becomes catastrophic when floods are unpredictable. The same uncertainty haunts Barani farmers, who depend entirely on rainfall for irrigation; their numbers are vast, and their vulnerability just as deep.

-

Gender invisibility: As established, excluding women from owning farmland is not just a social issue; it is a massive economic inefficiency that prevents a sizable chunk of the country’s potential participants’ wealth from being economically active.

-

The youth exodus: Young people are leaving the farm in droves. In rural Punjab, this is driven by a powerful economic and cultural pressure called ‘dekha dekhi’ (literally ‘seeing and copying’), a form of social contagion. Since the British resettlement of those displaced by the Tarbela and Mangla dams, especially near Mirpur, overseas migration has been seen as a golden ticket. Remittances elevate families in local prestige, and for young men, masculinity itself is proven through the ability to succeed abroad rather than remain tied to the land. This convergence of economic pressures and cultural ideals drains agriculture of its most adaptable generation at the very moment it needs innovation most.

-

The technology gap: Small farm sizes constrain mechanisation. A wealthy farmer on 50 acres buys a tractor. A smallholder on three acres cannot. He must rent from the wealthy farmer, but he gets the machinery last, often after his crop is past its prime, reducing its quality and price. The structural concentration of machinery in the hands of large landholders, therefore, reinforces productivity gaps and locks small farmers into cycles of low output and high vulnerability.

-

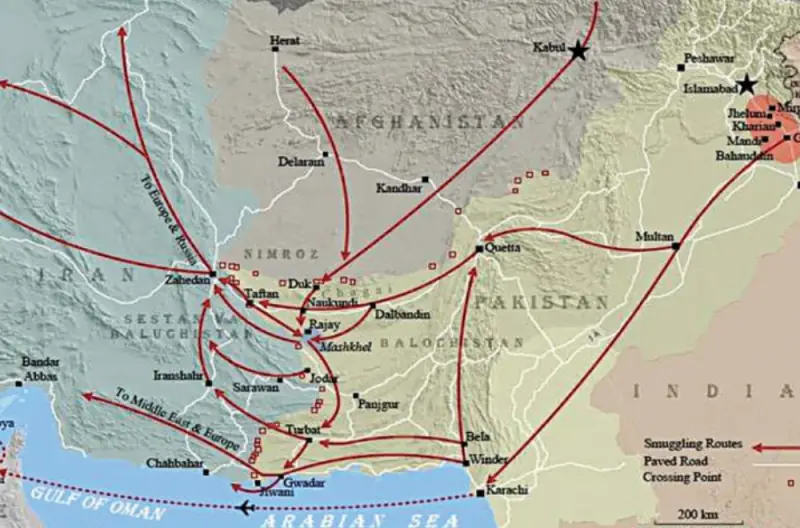

The arthi trap: Finally, even if a farmer overcomes other obstacles, he faces the arthi (middleman). Nearly 90pc of Pakistan’s smallholders are vulnerable to this system, with 48pc depending on arthis specifically for crop inputs. The mechanics of this trap are simple but effective: Before planting, a small farmer with no cash goes to the arthi for a loan for seeds and fertiliser. The arthi provides them at inflated prices and, often, low quality. Come harvest, the farmer must sell his crop back to that same arthi, who now sets a lowball price. The farmer remains trapped in a permanent cycle of debt, unable to accumulate enough profit to break free. Notice how the middleman profits twice: once by overcharging for inputs, again by underpaying for output.

A path to seven years of plenty

However, the census does not just diagnose problems; it illuminates corresponding interventions that can turn Pakistan’s liabilities into strengths.

-

Land consolidation: Instead of families fighting over scraps, the government can encourage cooperative farming, where ten farmers pool their three-acre plots to farm as one thirty-acre bloc, sharing a tractor and splitting the profits. Policymakers can revisit Ayub Khan’s 1960s experiment in cooperative farming, learning from its failures of trust and elite capture. A modern version could take the form of farm shareholding, where landowners hold equity in pooled enterprises rather than working isolated plots. Similar models exist abroad: US farmland REITs (real estate investment trusts) let investors own shares in agricultural portfolios, while China’s land shareholding cooperatives allow farmers to convert land rights into equity and dividends. With legal safeguards and transparency, Pakistan could adapt such a model to attract investment and give smallholders real stakes in larger, more efficient farms.

-

Water security: Scarcity requires both efficiency and replenishment. Poor legislation has reduced groundwater to concerningly low levels, especially in the Punjab province. District-level water budgets should be aligned with crop patterns. Investment in canal rehabilitation, groundwater recharge zones, check dams, and rainwater harvesting structures can stabilise supplies. Regulation of tubewell extraction and pricing reforms for pumping electricity can reduce unsustainable groundwater depletion. This governance failure stands out when compared with neighbouring Punjab in India, where stronger regulation has prevented groundwater decline from reaching Pakistan’s current severity.

-

Climate resilience: Crop diversification is the best insurance against climate shocks. Incentives for mixed cropping, promotion of climate-smart varieties, and support for localised seed banks can reduce vulnerability. Extension services must provide farmers with real-time weather and pest advisories to adapt quickly to shifting conditions.

-

Gender inclusion: Women’s inheritance rights must be enforced through both legal mechanisms and social change campaigns. Publicly funded legal aid for women in property disputes, targeted credit programs for female farmers, and capacity-building initiatives can begin to correct the imbalance. Recognising women as farmers in their own right would unlock underutilised productive capacity.

-

Engaging the youth: Agriculture must become attractive for younger generations, but this requires addressing both the economic and cultural dimensions that make irregular migration seem more appealing than farming. An economic deterrence strategy could redirect the 1.8 to 2.3 million rupees that aspiring migrants typically invest in illegal journeys by offering equivalent microfinance schemes in high-migration districts such as Gujrat, Sialkot, and Gujranwala for local agricultural ventures, supported by entrepreneurship programs led by the Small and Medium Enterprises Development Authority that highlight superior financial returns compared to deportation losses. At the same time, counter-narrative campaigns must tackle the dekha dekhi culture by mobilising Punjabi social media influencers to showcase successful young farmers and agribusiness entrepreneurs. Vloggers like Asad, who document the harrowing reality of failed ‘dunki’ (irregular migration) journeys, represent the kind of voices that can reshape perceptions, while agritech incubators and vocational programs reframe farming as a high-tech, profitable sector that restores local prestige to agricultural innovation.

-

Technology access: Shared machinery pools and leasing centres can democratise mechanisation. Cooperative ownership of tractors, threshers, and storage facilities would reduce costs and improve the timing of operations. Subsidised credit and training in digital farming tools can ensure smallholders are not permanently locked out of technological gains.

-

Market reform: Breaking this monopoly requires farmer empowerment. This means creating digital platforms that show real-time market prices, building public storage so farmers are not forced to sell at harvest, and, crucially, providing farmers access to formal bank credit so they are no longer dependent on these predatory credit-based relationships.

The choice ahead

The “seven lean years” may not be a future prophecy but a current reality. Unlike the biblical king, however, Pakistan has more than a dream; it has data. The census is a detailed diagnosis.

The question is no longer if there is a crisis, but whether Pakistan will use this clear warning to build resilience, or wait for the dream to become an irreversible reality.

Header Image: A grazing cow in the town of Naran, Kaghan Valley, Pakistan. Photo by Muhammad Ali on Unsplash

from Dawn - Home https://ift.tt/ktR8dJz

Comments

Post a Comment