The fear of smog has already started lingering upon us. We are once again bracing ourselves to choke in our own neglect. Are we doomed to suffer every year, through climate change, mismanagement, broken promises, or is it just bad luck?

In truth, it seems less a matter of fate and more the outcome of willful ignorance — an ignorance far from blissful, especially given that under Article 9 of Pakistan’s Constitution, the right to life inherently includes the right to a clean and healthy environment.

Numbers tell the story

This contradiction defines our new normal. For the past several winters, Pakistan has ranked as the third most polluted country in the world. Nowhere is this crisis more visible than in Lahore, the country’s second-largest city, where nearly 14 million residents are forced to breathe poison. It’s the most polluted city in the world and in the last five years, its air has met the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) minimum safety standards on only seven days.

The World Bank (WB) and the Air Quality Life Index (AQLI) estimates on Pakistan’s air pollution tell a story — one we’ve chosen to ignore for far too long.

The WB estimates that outdoor air pollution in Pakistan is responsible for 22,000 premature adult deaths and the loss of 163,432 disability-adjusted life years annually. Indoor air pollution, meanwhile, causes 28,000 deaths each year and leads to 40 million acute respiratory infections. Furthermore, the 2024 Air Quality Index (AQI) reported that poor air quality shortens average life expectancy by 3.9 years, rising to as much as seven years in heavily polluted cities such as Lahore, Peshawar, Gujranwala, and Rawalpindi.

The effects of air pollution extend far beyond human health, impacting the environment as well as the economy. According to the WB, environmental degradation costs the country around 7 per cent of its GDP, or about Rs365 billion per year, with the burden falling disproportionately on the poor. As an agrarian nation, Pakistan’s agricultural sector also suffers, with 2.6 billion people dependent on agriculture for their livelihood. Tropospheric ozone alone causes annual losses of approximately 110 million tonnes of key staple crops such as rice and wheat.

An administrative problem

The challenge of air pollution is neither new nor cyclical; it is a sustained environmental and public health crisis that demands long-term solutions. Its roots lie in systemic causes, ranging from natural factors such as temperature inversions and stagnant winds to human-driven sources like vehicular and industrial emissions, crop burning in agricultural regions, construction dust, combustion of biomass, and transboundary pollution from neighbouring countries such as India.

If we look at international examples such as England and China, it becomes evident that both countries tackled air pollution through strong, well-organised policies built on three key pillars: effective administration, robust governance, and consistent on-ground implementation. Pakistan could take cues from Britain’s landmark Clean Air Acts of 1956 and 1968, which curbed pollution. These specific laws enforced the use of smokeless fuels in urban areas and mandated factories to transition away from black smoke emissions.

Similarly, Beijing launched a series of forward-looking initiatives, including low-emission zones, an expanded urban rail network, and an advanced integrated air quality monitoring system. Established in 2016, this system leveraged cutting-edge technologies such as high-resolution satellite remote sensing and laser radar to combat air pollution. It also featured a dense PM2.5 monitoring network with more than 1,000 sensors strategically distributed across the city, allowing authorities to precisely identify when and where emissions peaked.

What these examples reveal is that cleaner air is not achieved through isolated fixes, but through strong systems that ensure accountability and follow-through. A discussion of the primary sectors of smog, then, must begin with the understanding that air pollution is, above all, an administrative problem.

Culprits of air pollution in Pakistan

Among the major sources of air pollution, it’s no mystery that transportation stands as the chief culprit behind smog. In Lahore alone, over 4.2 million motorcycles manoeuvre through its congested streets every day, averaging nearly two per household. Across Pakistan, the continued reliance on outdated Euro-II diesel fuel has further eroded air quality. The country’s freight and passenger fleets are still dominated by pre-Euro and Euro II trucks and buses, many of which release dangerously high levels of pollutants.

Weak regulatory enforcement and ineffective vehicle inspection systems allow these aging, smoke-belching vehicles to remain on the roads, making Pakistan’s transport sector one of its most stubborn and toxic sources of pollution.

Transport

Pakistan’s transport system is in desperate need of a major overhaul, particularly in terms of infrastructure. Despite the existence of national environmental quality standards, regular emission testing remains largely unenforced. A clear timeline must be established to phase out vehicles beyond a certain age, especially heavy-duty vehicles such as trucks. The installation of catalytic converters and the nationwide adoption of Euro-5 and Euro-6 standard fuels should be made mandatory. Electric buses, too, must become an integral part of Pakistan’s public transport network.

Encouragingly, the provincial government has launched a vehicle emission testing system in Punjab and begun deploying electric buses in the province. Punjab Chief Minister Maryam Nawaz has pledged to have 1,115 electric buses operational across Punjab by December.

It is critical for Pakistan to accelerate the adoption of a sustainable transportation system including electric buses and vehicles. It is not only essential for meeting the country’s commitments under its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, but also for easing the pressure on foreign reserves caused by Pakistan’s heavy dependence on imported oil.

Industries

Industrial emissions add yet another layer to the problem. Punjab’s industrial landscape is vast and diverse, with nearly 18,000 factories spread across multiple sectors. These include 718 chemical and petroleum units, 6,324 engineering units, 3,750 food, beverage, and tobacco units, 1,808 leather, rubber, and plastic units, 934 paper units, and 387 non-metal and mineral units.

However, while 560 industries in the Lahore division are formally registered, a sprawling informal sector, including thousands of brick kilns and small manufacturing units, continues to operate outside the regulatory framework. Most industries fail to comply with environmental standards and are often located within cities, dangerously close to residential areas, due to weak state enforcement. As a result, citizens are routinely exposed to pollutants such as sulphur dioxide and PM2.5, both major contributors to smog formation.

The Pakistan Environmental Protection Act of 1997 requires every industrial unit to self-monitor and report under smart rules, yet the reality paints a different picture — only 10 to 20pc of units actually comply. To address this, designated industrial zones should be established to prevent factories from operating near residential communities. Regular third-party audits and strict compliance monitoring must also be mandated to ensure adherence to environmental standards.

Moreover, while Article 9A of the Constitution guarantees the right to a clean and sustainable environment, the implementation of related policies and frameworks, such as the National Clean Air Policy, remains woefully inadequate.

Agriculture

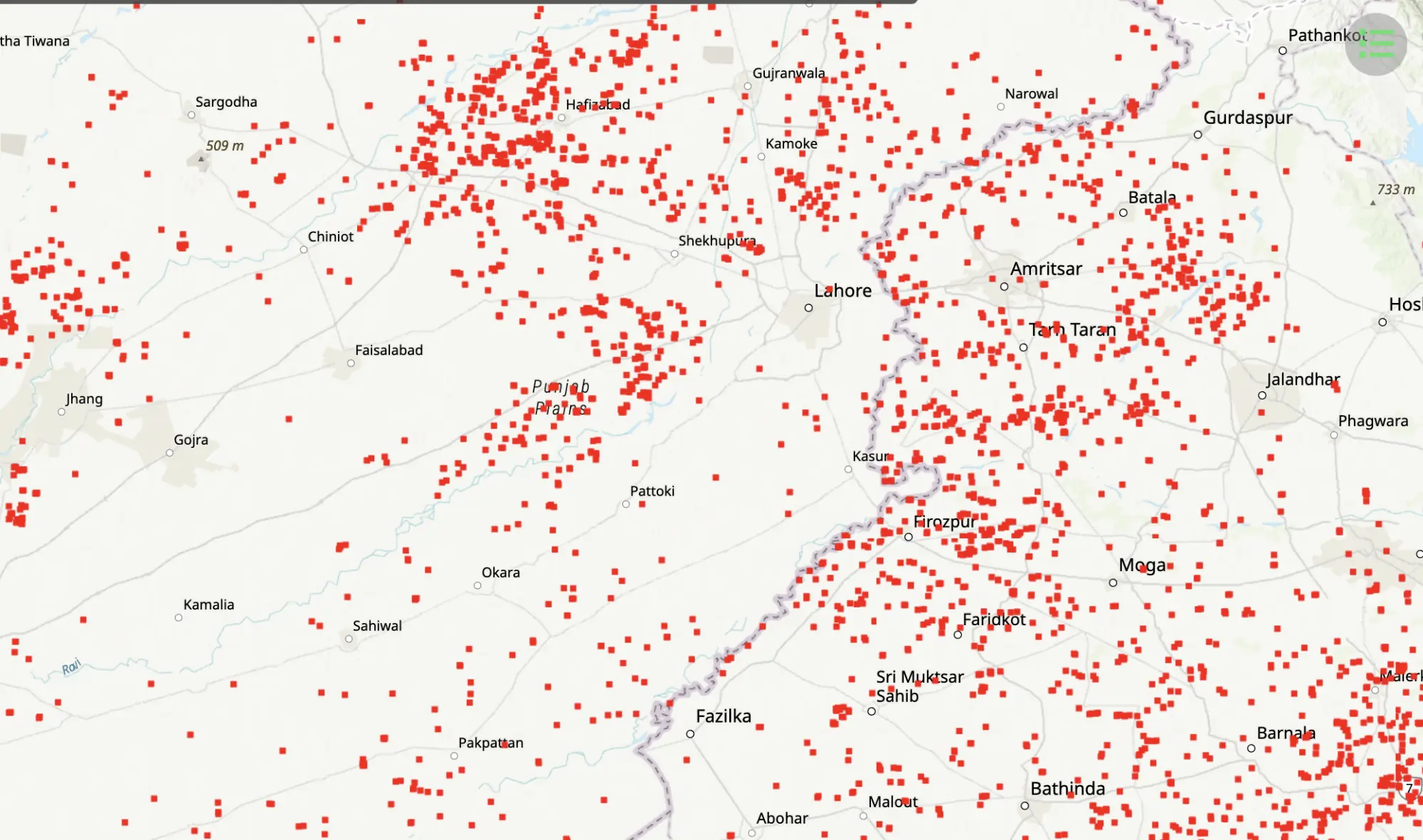

The agriculture sector, particularly crop burning, adds its own share to the haze. The primary source of this pollution is the post-harvest burning of crop residues by farmers in both Pakistan and India — a quick fix that clears the fields but poisons the air for the next cultivation cycle. Satellite imagery from Nasa Worldview, dated November 6, 2024, shows a thick blanket of smog engulfing Lahore, with clusters of fires scattered across the region between Delhi and Lahore.

Pakistan produces around 69 million tons of stubble annually, according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), contributing nearly 20pc of the country’s air pollution. To address this, the Punjab Clean Air Action Plan introduced a three-step policy aimed at discouraging stubble burning. Yet, it has failed to eliminate smog.

The government has distributed happy seeders, planters that shred crop residue and mulch it back into the soil, which have the potential to reduce carbon emissions by up to 78pc. However, the sheer volume of crop residue far exceeds the number of machines available, leaving a substantial gap between supply and demand. While these machines were made accessible to farmers in designated red zone districts, their cost remains prohibitive for small and marginal farmers. Making them more affordable would mark a major step toward sustainability, given the significant reduction in emissions they offer.

The government also attempted to impose fines of Rs50,000 per acre on offenders, but the policy fell short of its goals, hindered by inefficient enforcement mechanisms and the lack of affordable technological alternatives. This raises a critical policy question: should Pakistan rely more on carrots or sticks to promote climate-smart agricultural practices?

Construction sector

The construction sector, particularly brick kilns, is a major contributor to air pollution in Pakistan. Many brick kilns burn low-grade coal and waste materials, releasing large quantities of harmful pollutants into the atmosphere. Additionally, the incomplete combustion of biomass — commonly used as a cooking fuel in rural and low-income households — emits significant amounts of particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), soot, and other toxic substances. Together, these emissions have become major drivers of urban smog and deteriorating air quality across the country.

Pakistan should adopt modern, energy-efficient brick kiln technologies such as zigzag designs and expand the natural gas infrastructure nationwide to enable their widespread use. The government should also introduce incentives for the adoption of alternative clean fuels, particularly in areas without access to gas pipelines.

The analysis above suggests that if these sectors were modernised and effectively managed, Pakistan could potentially cut air pollution by as much as 50pc.

A holistic approach and climate diplomacy

Air pollution demands a holistic response, with a clear policy direction and multilateral solutions spanning all fronts including science, policy, and finance. Pakistan already sits on a pile of plans — the National Clean Air Policy, Punjab Clean Air Action Policy, SMOG Control Strategy 2024–25 — but policies without implementation are just paper promises.

Climate diplomacy should be pursued through a formal engagement with the government of India on air pollution, since it is a transboundary issue. Both countries can leverage joint air quality monitoring, data sharing and develop policies that can foster sustainable agricultural practices and reduce emissions.

Decentralised air plans should be adopted that engage stakeholders from all provinces. The private sector should engage in data generation and mapping emission hotspots, delivering research and carrying out advocacy campaigns.

We already know what must be done. The time to act is now because the smog won’t wait for our next committee meeting.

Header image: A view of Gurdwara Dera Sahib, Lahore Fort and a minaret of the Badshahi Mosque, seen amid smog in Lahore, Pakistan November 4, 2024. REUTERS/Nida Mehboob/File Photo

from Dawn - Home https://ift.tt/xj8wR90

Comments

Post a Comment