Washing and cooking at odd hours, storing food for days, timetabling routines — this is what the everyday life of hundreds of thousands of women looks like in Pakistan, who are forced to manage their lives around a tight electricity schedule. Like most other essentials, access to energy in Pakistan is not gender-neutral. And like every other instance, it is women who have to face the brunt of unreliable electricity, from interrupted housework to limited mobility and digital exclusion.

Nowhere is this clearer than in Lahore, where neighbourhood boundaries and social hierarchies create starkly unequal “energy lives”. To dig deeper, I set out to understand how this gender-energy nexus actually plays out across the city with my colleagues at the University of Cambridge and the Lahore University of Management Sciences.

Building on previous research on electricity demand in upper-class areas, we combined surveys, in-depth interviews, and neighbourhood walks to study five low-income neighbourhoods — Bahar Colony, Liaqatabad, Peer Colony, Charar Pind and Gajju Matta.

Our aim was simple: to understand how women in these ‘peripheries’ — socially and/or structurally marginalised low-income areas — secure and use energy at home, at work and in public, and what that means for their daily lives and their overall empowerment.

A city of uneven development

Lahore’s rich colonial history, post-colonial expansion and decades of rural-to-urban migration have produced a city with distinct enclaves. Affluent gated communities, older cantonment neighbourhoods and industrial belts sit alongside dense slums and semi-informal settlements that blur the line between ‘planned’ and ‘unplanned’.

This diversity is marked by stark contrasts in infrastructure provision: while the city’s more affluent housing developments typically enjoy more reliable power supply, piped gas and maintained roads, many low-income and loosely planned areas — even those adjacent to affluent urban cores — remain peripheral and underserved. The result is spatially uneven energy access with distinctly gendered effects.

For example, in Charar Pind, a narrow-alleyed village, women belonging to low-income backgrounds are encircled by Lahore’s prime real estate community, the Defence Housing Authority (DHA). Despite their proximity to the shiny suburban locality, they rely on patchy connections and precarious services in their own settlements.

“There is mostly no gas in the morning, so my father and brother leave for work without breakfast … we can only cook when gas is available,” a participant told us. “How can we use a heater?”

Such disparities translate into compounded time poverty for women, revealing how uneven urban development materialises into uneven energy provision.

The power divide

While stark differences exist in energy services between urban cores and the outskirts, our study found that internally, even these peripheries are diverse.

In Liaqatabad alone, household incomes varied 20-fold, while Gajju Matta village, located in the Nishtar tehsil of Lahore, recorded the lowest average incomes and the weakest provision of basic utilities — roads, drainage and electricity. This heterogeneity undermines any idea of “the urban poor” as a single, uniform group and signals that geographical location and local governance shape material conditions as much as household income does.

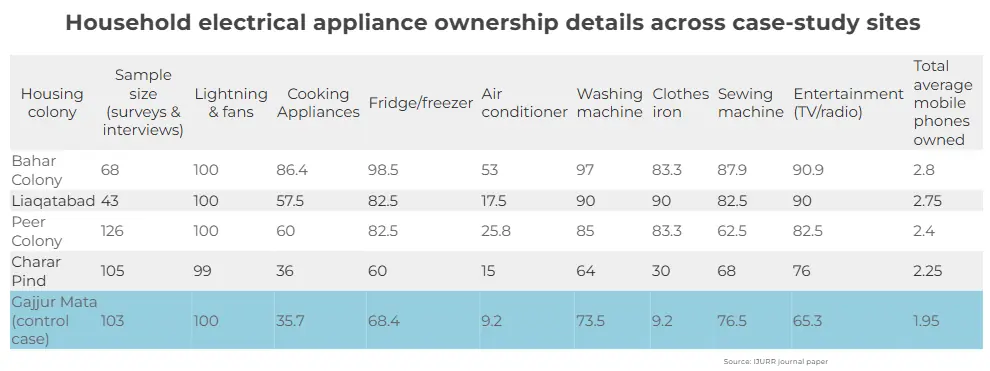

A deeper dive into our five low-income neighbourhoods revealed that ownership of electrical appliances was consistently lower in households with lower income, tenancy residence (as opposed to house ownership), and less educated women (below grade 10 education).

There was also a divide among those who owned appliances; households in Bahar Colony — located less than a kilometre south of what used to be the family residence of Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and his brother Nawaz Sharif — reported high access to refrigerators/ freezers at 98.5 per cent, and air-conditioners at 53pc, while Gajju Matta lagged sharply with 68.4pc fridges and freezers and 9.2pc ACs.

Cooking appliances such as microwaves, rice-cookers and kettles were also clustered near urban cores — 86.4pc in Bahar Colony and 60pc in Peer Colony — and thinned out at the edge — 35.7pc in Gajju Matta.

In terms of digital access, we found that while women had less access to mobile phones and internet/ wifi compared to men across all sites, this gap exhibited significant geographic underpinnings. In Bahar Colony, 88pc of households had at least one woman who owned a mobile phone, while 79pc had at least one woman using the internet. In Gajju Matta, these figures dipped to 35pc and 12pc, respectively.

“All of us have mobile phones,” a Bahar Colony respondent told us. “I have this small keypad phone; I like it because I don’t know how to use smartphones, but my kids have smartphones.”

Another woman in Charar Pind described stricter control: “My uncle’s [phone], only he has the internet … I’m not allowed. Besides, we can’t afford so many phones.”

Women’s workplace location also matters. Women who travelled farther — to core neighbourhoods or the city centre — reported higher access to digital tools, i.e. mobile 73pc and internet/ wi-fi 50pc, than women working from home or within their colonies, of which 56pc and 40pc had access to mobile phones and internet, respectively.

Urban to rural energy flow

Interestingly, the proximity to core areas raised the odds of owning an appliance, simultaneously building energy-related knowledge and aspirations. Many low-income women employed in domestic services in Model Town or DHA learnt to operate appliances they did not own, including washing machines, microwaves, kettles, and air conditioners.

“No one in our area knows how to use these modern appliances. We learn from our workplaces,” a woman in Charar Pind explained, before listing the foods she had learnt to cook and the hygiene routines she had adopted.

Similarly, a nurse from Bahar Colony added: “I’ve learnt how to use a microwave … kettle, AC, which I don’t have at home, but I know how to use.”

Sometimes these ties translated into material gains. “I bought my employer’s old fridge on instalments,” said another resident of Charar Pind who works as a housemaid in a nearby DHA home. “We didn’t have a fridge before … now, they take a percentage of my salary as instalments.”

According to DHA’s Security Office, more than 300 women enter the posh neighbourhood daily through barricaded gates from Charar Pind and Peer Colony for income-generating work — movements that are closely monitored and individually logged. These figures underline both the opportunity and the asymmetry: affluent areas rely on women’s labour from their less-affluent neighbourhoods, yet their access remains contingent on the discretion of estate authorities.

Living near high-income areas also improved women’s access to public amenities that depend on reliable energy — healthcare, religious facilities, and even recreational spaces and parks. In proximal sites, 72.4pc of women reported access to health facilities (versus 33.6pc in the control), 52pc reported access to religious facilities (versus 28.5pc), and 36.6pc to open/green spaces (versus 18.3pc).

Women in these sites were also more likely to be in paid work, with only 27pc unemployed, compared to the 53pc unemployed in other low-income areas, highlighting the glaring link between employment, mobility and infrastructures.

Gendered norms and the salience of identity

During the course of our research, we also found that women’s electricity access was shaped by both social identity and location. Even within the same household, age and status matter: younger women — especially daughters-in-law in joint families — often have less autonomy over appliance use and electricity spending.

“My mother-in-law washes her clothes in the machine; I wash mine by hand … she doesn’t allow me to use the machine,” said a woman residing in Peer Colony, situated near DHA Phase 1 and the cantonment.

Religion also emerged as a key factor. In interviews at Gajju Matta, some Muslim respondents described strict limits on mobility. “We are Syeds … we never go outside. My husband brings everything,” one woman said.

At the community level, mosques across the five sites chosen by us offered no dedicated space for women, curtailing their access to public religious facilities and to the information flows and networks that form around them. Meanwhile, churches in Christian-majority localities did provide such spaces.

On average, Christian women in our sample reported higher scores for control over finances, electricity decisions and freedom of movement than Muslim women. This shows how religious norms and local institutional designs can combine to shape access to public and energy-dependent spaces.

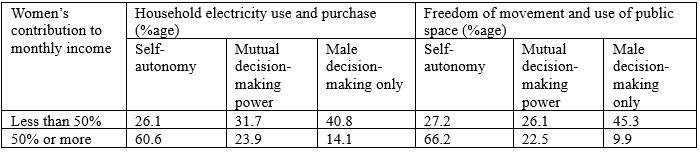

Our data showed that the link between household prosperity and women’s energy empowerment is not linear. In poorer households, below the 25th percentile, more women worked for money; those who contributed 50pc or more of household income reported far greater self-autonomy over electricity purchases at 61pc and freedom of movement at 66pc, as compared to women contributing less than half at 26pc and 27pc, respectively.

Meanwhile, some unemployed women in financially stable low-income households possessed more appliances at home but had less mobility and weaker public-space access. This shows that household income, employment, and access to energy across private/public spaces interlink in complex, context-specific ways, shaped by norms, bargaining power, and place.

Why these numbers matter

Not all city neighbourhoods are created equal. Our study shows that in Lahore, a woman’s location on the map shapes her “energy life” — whether she has access to labour-saving appliances, how long she endures load-shedding, which jobs she can reach, and whether schools, clinics and parks are within safe, affordable reach.

These differences are layered with identity, including income, class, religion, and employment, thus creating complex intersections of gender, energy, and space use. Seeing energy as a purely technical issue undermines these social realities.

Moreover, treating cities as uniform masks these disparities. By mapping how energy flows, and doesn’t flow, from the home to the city, and both within and across neighbourhoods, policymakers and planners can better address the root causes of gendered energy inequities, rather than offering one-size-fits-all solutions. This is essential for Pakistan to move towards a fairer and more sustainable energy future.

Header image adapted from Shutterstock

from The Dawn News - Home https://ift.tt/bWq7OC8

Comments

Post a Comment